Curling and Young's Shipyard existed in Limehouse Docks in East London on the River Thames from circa 1800 through to 1855. The following extract concerning the history of Limehouse Hole, written and posted by Mick Lemmerman as part of his history of East London and Dockland areas, covers the story of the shipyard.

Limehouse Hole

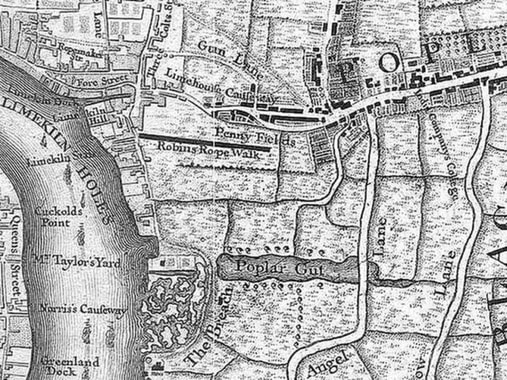

Limekin Holes circa 1745

Limekin Holes circa 1745

The origins of the name Limehouse Hole are not certain. This following 1745 map mentions Limekiln Holes, in the plural, and possibly referring the stretch of river, rather than a place on dry land. My own theory is that a hole was a small harbour, a place to lay up ships, as in Mousehole in Cornwall (mind you historians debate the origin of this name too). This area was, after all, from the 17th century a plying place for watermen and it later became densely filled with shipyards and other dock-related industries.

Limehouse Hole stretched from Limekiln Dock in the north to the Poplar Breach in the south which is just north of the present-day Westferry Circus.

As London’s riverside was developed, and Limehouse spread eastwards in the seventeenth century, Limehouse Hole was built up with shipping-related enterprises. These characterized the area into the twentieth century. There were shipbuilders, barge-builders, boat-builders, ropemakers, sailmakers, mastmakers, blockmakers and ship-chandlers, as well as general wharfingers.

The eight acres of riverside land immediately south of the boundary between Limehouse and Poplar, empty save perhaps for a few small houses behind the river wall, were leased by Sir Edward and Sir John Yate to John Graves in 1633. Graves was a shipbuilder at the yard on the north side of the boundary, later known as Limekiln Dockyard and then as Dundee Wharf. In 1664 Samuel Pepys visited Margetts’s ropeyard and apparently decided to use it to supply the Navy. In 1662 Margetts acquired the freehold of Graves’s eight acres, with an additional 2½ acres to the east. The estate subsequently passed by marriage to Cornelius Purnell, a Portsmouth shipwright. His son sold part of it in 1717 to Philip Willshire, who acquired the remainder in 1723. The estate passed through Willshire’s family to Edward Emmett, whose heirs retained the property until 1809, when it was sold off in parcels.

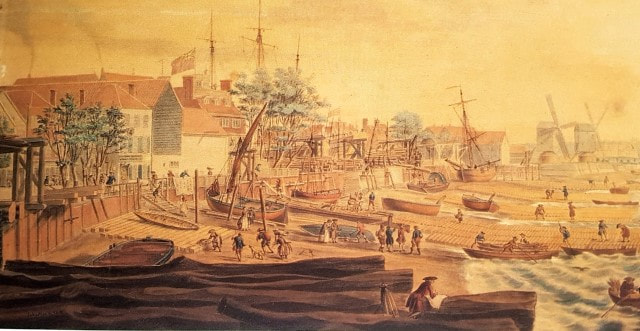

The foreshore of Robert Batson’s Yard, as shown above, is full of timber, imported for the construction of ships (mostly warships and East Indiamen). Batson was a substantial Island landowner – the first residential streets in Millwall were built on his land: Robert and Alfred Street are named after his sons, and later renamed Cuba and Tobago Street respectively. At the end of Cuba Street was formerly Batson’s Wharf (absorbed into Lenanton’s Yard), while there was once a a Batson’s Street off Three Colt Street. Hood’s painting shows Limehouse Hole Stairs on the left. These were at the river end of Thames Place, which connected with Emmet Street, and which disappeared not that long ago. Also notable is the public house at the top of the stairs; possibly known as the White Lion at the time, it would later be named the Chequers, and then the Horns and Chequers.

Curling & Young’s Shipyard

In 1800 Batson’s yard was transferred to Cox, Curling & Company, shipbuilders, previously based at Duke Shore, Limehouse, and across the river. They enlarged the dry docks and demolished the house. The company was controlled in the early nineteenth century by Robert Curling and William Young. William Curling (c1770–1853). Jesse Curling and George Frederick Young succeeded them and from c1820 the firm was known as Curling, Young & Company. They built East and West Indiamen and, from the late 1830s, large merchant steamships, all of them of timber, not iron. The yard became known as Limehouse Dockyard, and the management as Young, Son & Magnay from about 1855, by which time at least one of the slips was covered with open-sided shedding. The firm continued to build large timber ships, but this was a declining section of the shipbuilding industry.

Curling, Young and Co

According to Grace's Guide to British Industrial History Curling, Young and Co built the following ships and boats:

1824 - Built schooner “Colombian Packet”, 346 tons

1825 – Built ship “Hindostan” at Limehouse, 500 tons

1826 – Built barque “Achilles”, 196 tons

1827 – Built ship “James Cruikshank”, 319 tons

1829 – Built barque “Kingdown”, 346 tons

1830 – Built sailing vessel “Walmer, 369 tons, built for Southern whale fishery. Built ship “John Pink”, 283 tons

1834 – Built ship “Louisa Baillie”, 412 tons, Built schooner “Lady Katherine Barham” at Limehouse, 412 tons, built ship “Justina”

at Limehouse, 412 tons

1835 – Built wood steamer “Water Witch”, 275 tons, Built wood steamer “Vivid”

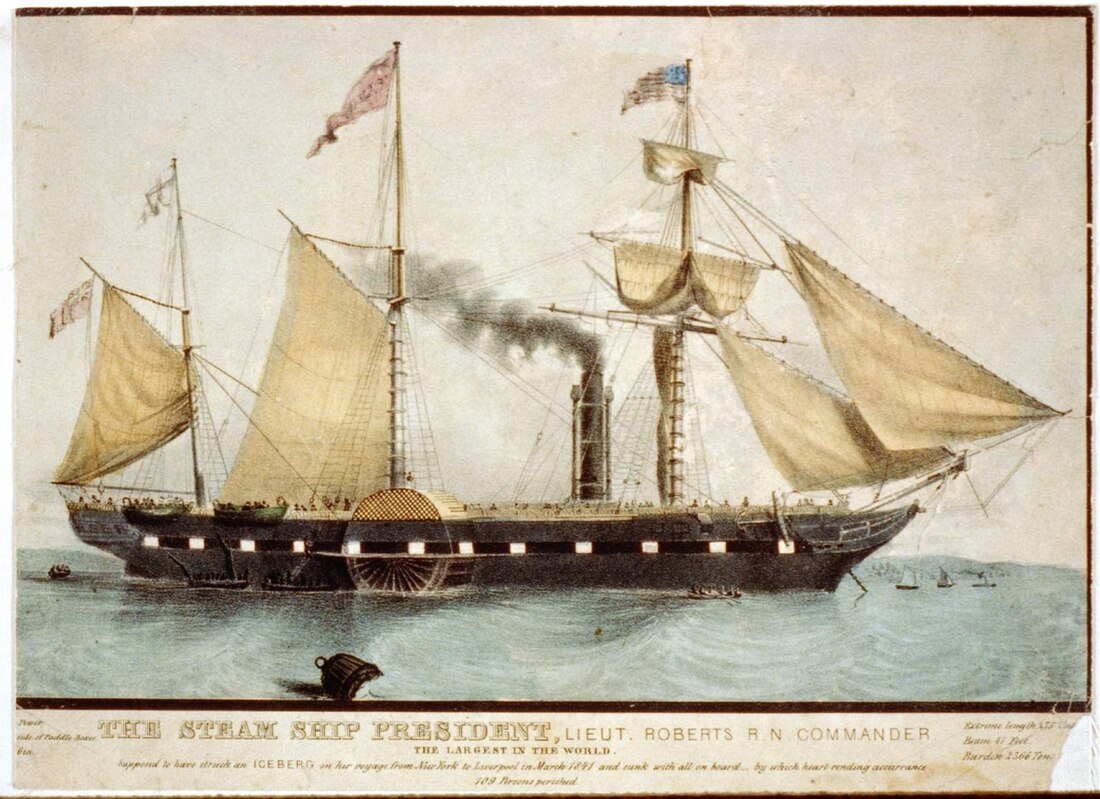

1840 "THE PRESIDENT STEAM-SHIP. ( From the Albion). The President steam-ship, Lieutenant Fayrer, R.N., commander, is sister

ship to the British Queen, both belonging to he British and American Steam Navigation Company.

The President was intended to run between Liveroool and New York, and was believed to be the largest steamer afloat, being of 2366 tons register, and having engines of 600 horse power. The ship was built in London, by Messrs. Curling, Young, & Co., who are also the builders of the British Queen. Both vessels were designed Mr. Maccregor Laird, and laid down from his drawings. They reflect the highest credit on his judgment and skill.

The engines were constructed by our celebrated townsmen, Messrs. Fawcett, Preston and Co.: they are the largest marine engines yet made, having cylinders eighty inches diameter and seven and half feet long of stroke.

The accommodations for passengers in this magnificent vessel were of the very first order.

Original caption: “The Steam Ship President, Lieut. Roberts R.N. Commander. The Largest in the World. Supposed to have struck an ICEBERG on her voyage from New York to Liverpool in March 1841 and sunk with all on board ... by which heart-rending accurrence [sic] 109 Persons perished. Extreme length 275 Feet; Beam 41 Feet; Burden 2366 Tons.” (The original's left margin has been cut off.) The supposition of an iceberg as the culprit was a later notion; the available evidence makes it unlikely.